| rosanista.com | ||

| Simplified Scientific Christianity |

As we look about us in the material universe we see a myriad of forms and all these forms have a certain color and many of them emit a definite tone; in fact all do, for there is sound even in so-called inanimate Nature. The wind in the tree tops, the babbling of the brook, the swell of the ocean are all definite contributions to the harmony of nature.

Of these three attributes of nature, form, color, and tone, form is the most stable, tending to remain in statu quo for a considerable time and changing very slowly. Color on the other hand, changes more readily: it fades, and there are some colors that change their hue when held at different angles to the light; but tone is the most elusive of all three; it comes and goes like a will-o'-the-wisp, which none may catch or hold.

We also have three arts which seek to express the good, the true and the beautiful in these three attributes of the World Soul: namely, sculpture, painting and music.

The sculptor who deals with form seeks to imprison beauty in a marble statue that will withstand the ravages of time during millenniums; but a marble statue is cold and speaks to but a few of the most evolved who are able to infuse the statue with their own life.

The painter's art deals preeminently with color; it gives no tangible form to its creations; the form on a painting is an illusion from the material point of view, yet it is so much more real to most people that the real tangible statue, for the forms of a painter are alive; there is living beauty in the painting of a great artist, a beauty that many can appreciate and enjoy.

But in the case of a painting we are again affected by the changeableness of color; time soon blots out its freshness, and at the best, of course, no painting can outlast a statue.

Yet in those arts which deal with form and color there is a creation once and for all time; they have that in common, and in that they differ radically from the tone art, for music is so elusive that it must be recreated each time we wish to enjoy it, but in return it has a power to speak to all human beings in a manner that is entirely beyond the other two arts. It will add to our greatest joys and soothe our deepest sorrows; it can calm the passion of the savage breast and stir to bravery the greatest coward; it is the most potent influence in swaying humanity that is known to man, and yet, viewed solely from the material standpoint, it is superfluous, as shown by Darwin and Spencer.

It is only when we go behind the scenes of the visible and realize that man is a composite being, spirit, soul and body, that we are enabled to understand why we are thus differently affected by the products of the three arts.

While man lives an outward life in the form world, where he lives a form life among other forms, he lives also an inner life, which is of far greater importance to him; a life where his feelings, thoughts and emotions create before his "inner vision" pictures and scenes that are ever changing, and the fuller this inner life is, the less will the man need to seek company outside himself, for he is his own best company, independent of the outside amusement, so eagerly sought by those whose inner life is barren; who know hosts of other people, but are strangers to themselves, afraid of their own company.

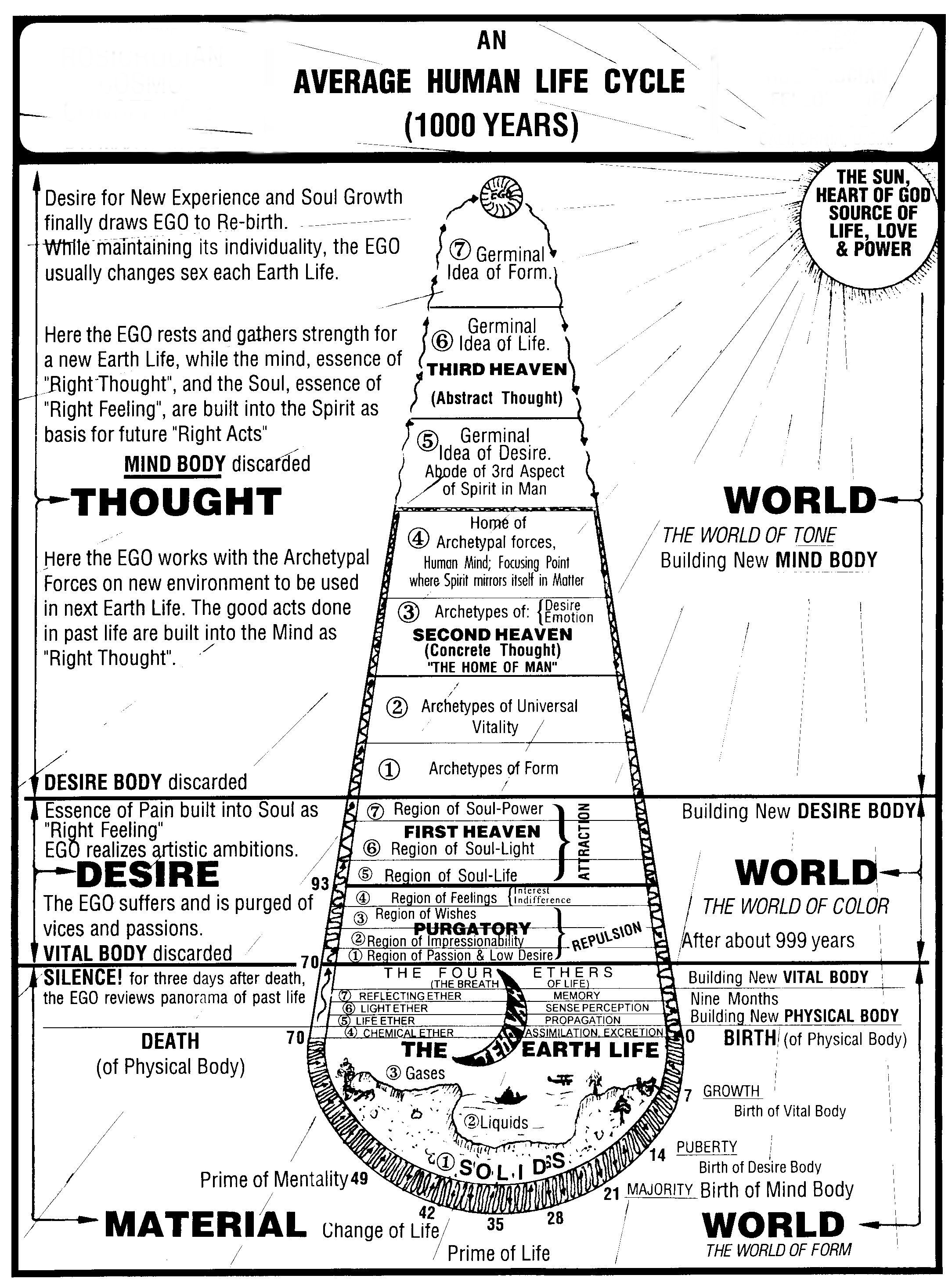

If we analyze this inner life we shall find that it is twofold: (1) The soul life, which deals with the feelings and emotions: (2) the activity of the Ego which directs all actions by thought.

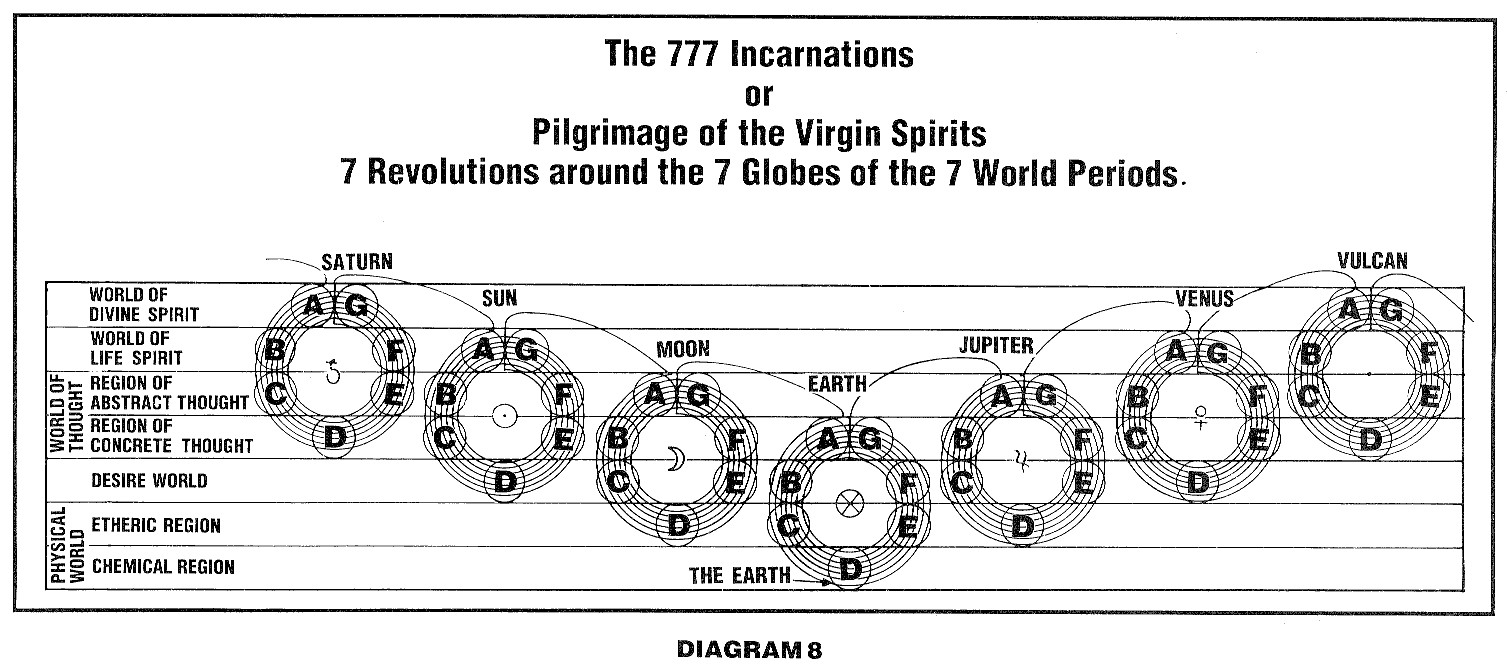

Just as the material world is the base of supply whence the materials for our dense body have been drawn, and is preeminently the world of form, so there is a world of the soul, called the Desire World among the Rosicrucians, which is the base from whence the subtle garment of the Ego, which we call the soul, has been drawn, and this world is particularly the world of color. But the still more subtle World of Thought is the home of the human spirit, the ego, and also the realm of tone. Therefore, of the three arts, music has the greatest power over man; for while we are in this terrestrial life we are exiled from our heavenly home and have often forgotten it in our material pursuits, but then comes music, a fragrant odor laden with unspeakable memories. Like an echo from home it reminds us of that forgotten land where all is joy and peace, and even though we may scout such ideas in our material mind, the Ego knows each blessed note as a message from the homeland and rejoices in it.

This realization of the nature of music is necessary to the proper appreciation of such a great masterpiece as Richard Wagner's Parsifal, where the music and the characters are bound together as in no other modern musical production.

Wagner's drama is founded upon the legend of Parsifal, a legend that has its origin enshrouded in the mystery which overshadows the infancy of the human race. It is an erroneous idea when we think that a myth is a figment of human fancy, having no foundation in fact. On the contrary, a myth is a casket containing at times the deepest and most precious jewels of spiritual truth, pearls of beauty so rare and ethereal that they cannot stand exposure to the material intellect. In order to shield them and at the same time allow them to work upon humanity for its spiritual upliftment, the Great Teachers who guide evolution, unseen but potent, give these spiritual truths to nascent humanity, encased in the picturesque symbolism of myths, so that they may work upon our feelings until such time as our dawning intellects shall have become sufficiently evolved and spiritualized so that we may both feel and know.

This is on the same principle that we give our children moral teachings by means of picture books and fairy tales, reserving the more direct teaching for later years.

Wagner did more than merely copy the legend. Legends, like all else, become encrusted by transmission and lose their beauty and it is a further evidence of Wagner's greatness that he was never bound in his expression by fashion or creed. He always asserted the prerogative of art in dealing with allegories untrammeled and free.

As he says in Religion and Art: "One might say that where religion becomes artificial, it is reserved for art to save the spirit of religion by recognizing the figurative value of the mythical symbol, which religion would have us believe in a literal sense, and revealing its deep and hidden truths through an ideal presentation. ....Whilst the priest stakes everything on religious allegories being accepted as matters of fact, the artist has no concern at all with such a thing, since he freely and openly gives out his work as his own invention. But religion has sunk into an artificial life when she finds herself compelled to keep on adding to the edifice of her dogmatic symbols, and thus conceals the one divinely true in her, beneath an ever-growing heap of incredibilities recommended to belief. Feeling this, she has always sought the aide of art, who on her side has remained incapable of a higher evolution so long as she must present that alleged reality to the worshiper, in the form of fetishes and idols, whereas she could only fulfill her true vocation when, by an ideal presentment of the allegorical figure, she led to an apprehension of its inner kernel — the truth ineffably divine."

Turning to a consideration of the drama of Parsifal we find that the opening scene is laid in the grounds of the Castle of Mount Salvat. This is a place of peace, where all life is sacred; the animals and birds are tame, for, like all really holy men, the knights are harmless, killing neither to eat nor for sport. They apply the maxim, "Live and let live," to all living creatures.

It is dawn and we see Gurnemanz, the oldest of the Grail Knights, with two young squires under a tree. They have just awakened from their night's rest, and in the distance they spy Kundry coming galloping on a wild steed. In Kundry we see a creature of two existences, one as servitor of the Grail, willing and anxious to further the interests of the Grail Knights by all means within her power; this seems to be her real nature. In the other existence she is the unwilling slave of the magician Klingsor and is forced by him to tempt and harass the Grail Knights whom she longs to serve. The gate from one existence to the other is "sleep," and she is bound to serve him who finds and wakes her. When Gurnemanz finds her she is the willing servitor of the Grail, but when Klingsor evokes her by his evil spells he is entitled to her services whether she will or not.

In the first act she is clothed in a robe of snake skins, symbolical of the doctrine of rebirth, for as the snake sheds its skin, coat after coat, which it exudes from itself, so the Ego in its evolutionary pilgrimage emanates from itself one body after another, shedding each vehicle as the snake sheds its skin, when it has become hard, set and crystallized so that it has lost its efficiency. This idea is also coupled with the teachings of the Law of Consequence, which brings to us as reaping whatever we sow, in Gurnemanz's answer to the young squire's avowal of the distrust in Kundry:

When Kundry comes on the scene she pulls from her bosom a phial which she says she has brought from Araby and which she hopes will be a balm for the wound in the side of Amfortas, the King of the Grail, which causes him unspeakable suffering and which cannot heal. The suffering king is then carried on stage, reclining on the couch. He is on his way to his daily bath in the near-by lake, where two swans swim and make the waters into a healing lotion which assuages his dreadful sufferings. Amfortas thanks Kundry, but expresses the opinion that there is no relief for him till the deliverer has come, of whom the Grail has prophesied, "a virgin fool, by pity enlightened." But Amfortas thinks death will come before deliverance.

Amfortas is carried out, and four of the young squires crowd around Gurnemanz and ask him to tell them the story of the Grail and Amfortas' wound.

(Note: "Parsifal" is the legend of the Rosicrucian Teachings. The student will readily see its analogy to spiritual attainment through a life of purity and service. The aspirant [the Grail Knights] by overcoming the lower nature [Klingsor] and gaining control of the dense body [Kundry], is able through a life of purity and service to raise the spinal fire to the head [Mt. Salvat] and attain liberation. Thus the new race, symbolized by Parsifal, sees the suffering caused by abuse of sex and lifts itself to passionless generation in harmony with the laws of nature.)

(You are welcome to e-mail your answers and/or comments to us. Please be sure to include the course name and Independent Study Module number in your e-mail to us.)

1. Name the three attributes of nature and the arts which express them.

2. Which of the arts is most potent in swaying humanity?

3. Explain the reason for this.

4. What is the true nature of the myth?

5. Describe Mt. Salvat.

6. Who was Kundry?

7. What was to be the character of the deliverer of Amfortas?

|

|

|

|

|

Contemporary Mystic Christianity |

|

|

This web page has been edited and/or excerpted from reference material, has been modified from its original version, and is in conformance with the web host's Members Terms & Conditions. This website is offered to the public by students of The Rosicrucian Teachings, and has no official affiliation with any organization. | Mobile Version | |

|