| rosanista.com | ||

| Simplified Scientific Christianity |

—Wordsworth

When Siegfried leaves the rock of the Valkuerie and reaches the worldly court of Gunther, he is given a drink calculated to make him forget all about his past life and Brunhilde, the spirit of truth, whom he had won for his very own.

It is usually supposed that the doctrine of rebirth is taught only in the ancient religions of the Orient, but a study of the Scandinavian mythology will soon rout that misconception. Indeed, they believed in both rebirth and the Law of Cause and Effect as applied to moral conduct, until Christianity clouded these doctrines, for reasons given in The Rosicrucian Cosmo-Conception (p. 167). And it is curious to read of the confusion caused when the ancient religion of Wotan was being superseded by Christianity. Men believed in rebirth in their hearts, but repudiated it outwardly, as the following story told of Saint Olaf, King of Norway, one of the earliest and most zealous converts to Christianity, will show; when Asta, the Queen of King Harold, was in labor but could not bring birth, a man came to the court with some jewels, of which he gave the following account: King Olaf Geirstad, who had reigned in Norway many years before and was the direct ancestor of Harold, had appeared to him in a dream and directed him to open the great earth-mound in which his body lay, and having severed it from the head with a sword, to convey certain jewels, which he would find in the coffin, to the queen, whose pains would then cease. The jewels were taken into the queen's chamber, and soon after she as delivered of a male child, whom they named Olaf. It was generally believed that the Spirit of Olaf Geirstad had passed into the body of the child, who was named after him.

Many years after, when Olaf had become King of Norway, and had embraced Christianity, he rode one day, as he often did, by the mound where his ancestor lay, and a courtier, who was with him at the time asked,

"Is it true, my lord, that you once lay in this mound?"

"Never," replied the king, "has my Spirit inhabited two bodies."

"Yet, it has been reported that you have been heard to say, on passing this mound, 'Here was I. Here I lived.'"

"I have never so said," returned the king, "and never will I say so."

He was much discomfited, and rode hastily away, presumably to avoid discussion of an inward conviction which all the dogmas of the new faith could not eradicate.

As a matter of fact, all ancient people, whether in the East or in the West, knew much about birth and death which has been forgotten in modern times, because second sight was more prevalent then. To this day, for instance, many peasants in Norway assert ability to see the Spirit passing out of the body at death, as a long narrow white cloud, which is, of course, the vital body; and the Rosicrucian Teaching—that the deceased hover around their earthly abode for some time after death, that they assume a luminous body and are sorely afflicted by the grief of dear ones—was common knowledge among the ancient Norsemen. When the deceased King Helge of Denmark materialized to assuage the grief of his widow, and she exclaimed in anguish "The dew of death has bathed his warrior body," he answered:

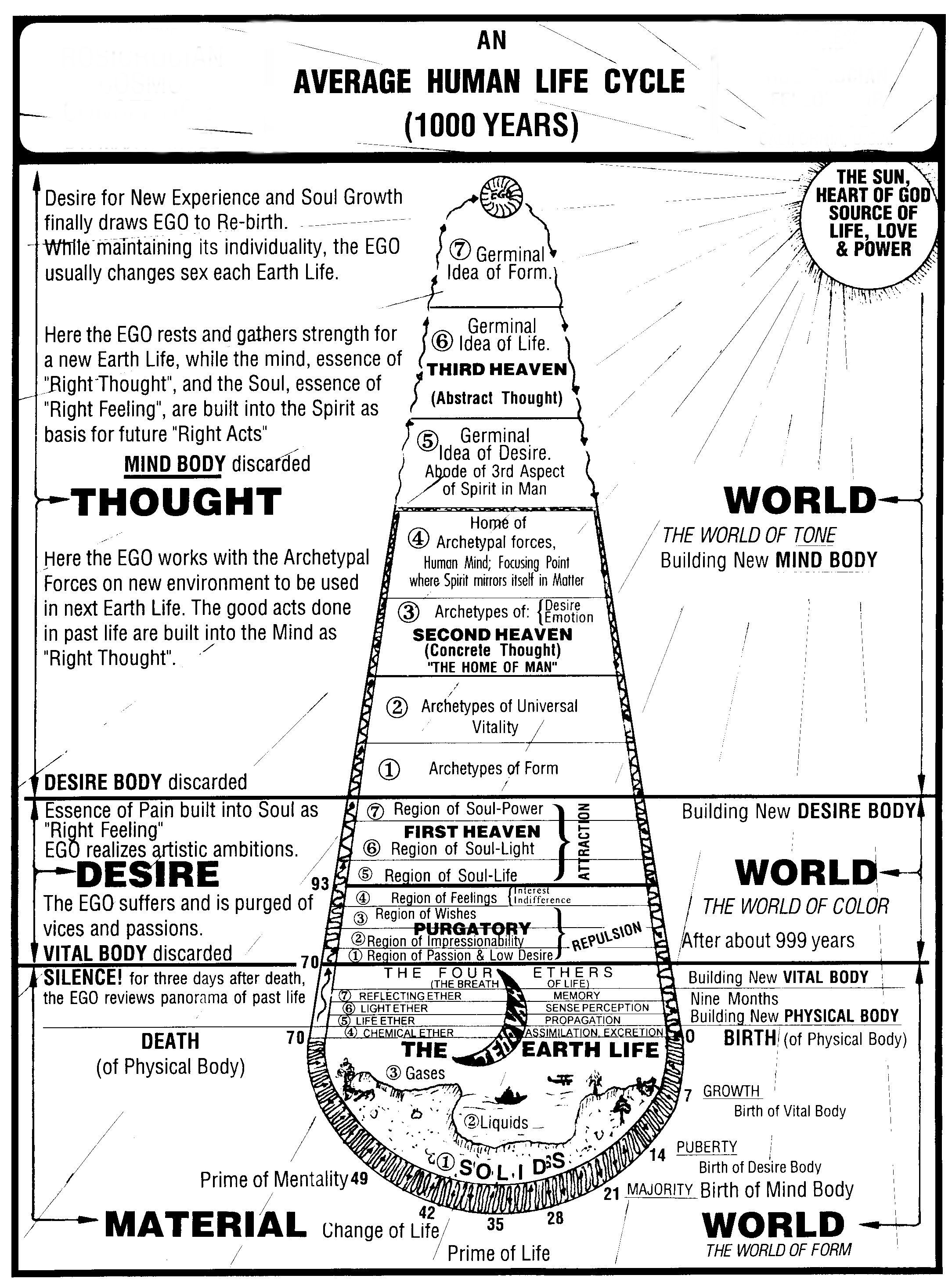

Students, when they realize the fact of rebirth, generally wonder why the memory of past lives is blotted out, and many are filled with an almost overpowering desire to know the past. They cannot understand the benefit derived from the lethal drink of forgetfulness, and they look with envy at people who claim to know their past lives—when they claim to have been kings, queens, philosophers, priests, et cetera. There is, however, a most beneficent purpose in this forgetfulness, for no experience is of value in life except for the impress which it leaves by the purgatorial or heavenly post-mortem experience. This impress then acts in such a manner that at the proper time it directs, warns, or urges a certain line of action, and this warning, or urge, though dissociated from the experience, or rather for the reason that it is dissociated from the experience wherefrom it was extracted, acts with a quickness greater than that of thought.

To make this point clear we may perhaps liken this record, graven upon our subtler vehicles, to a phonograph record, which playing, will cause a battery of tuning forks placed near it to vibrate as each note is struck. From the outward point of view there seems to be no reason why a certain indentation on a phonographic record should correspond to a certain one on the tuning fork, and when the needle falls into that indentation, a definite sound should be produced which sets the tuning fork vibrating. But whether we understand it or not, demonstration shows that there is a tie of tone between that little indentation and the tuning fork. And this does not depend upon a knowledge of how the impress came to be imprinted on the record, or what caused the tuning fork to respond to that vibration. It is there, whether we know all the facts about it, or not.

Similarly, when we have had a certain experience in life, be it joyful or the reverse, it is condensed in the post-mortem experience, leaving an impress upon the soul to warn, if the experience is purgatorial; to urge, if heavenly. And in a later life, when an experience comes up similar to the one which caused the impress, the vibration is sensed by the soul, it awakens the tone of pain or pleasure, as the case may be, in the record of the past life, far more speedily and accurately than if the experience itself were called up before our mind's eye. For we might not, even at the present time, be able to see the experience in its true light while we are hampered by the veil of flesh, but the fruit of the experience, gathered in heaven or hell, tells us unerringly whether to emulate our past, or shun it.

Moreover, supposing we did know our past lives: that by our present endeavors to live well and worthily we had acquired that faculty. Supposing that we had lived lives of debauchery, cruelty, crime, and selfishness! If people now despised us accordingly, we would then hold that they ought not to judge us by the past—that they were wrong in ostracizing us. We would contend that our present life of worthy endeavor should be made the basis of judgment, to the exclusion of former conditions, and in this we should be perfectly right. But then, for the same reason, why should we claim honor in the present life, adulation or admiration, because in the past life we were kings and queens? Even if it were true that we had held such positions, why should we lay ourselves open to the ridicule of skeptics by telling such stories? So, whether we have memory of our past lives or not, it is better to concentrate our efforts upon the highest possibilities of today.

There is no doubt that one who is able to search the Memory of Nature, and who does so for the sake of investigation in connection with the progress and evolution of man, will, at some time or other, come into touch with glimpses of his or her own past. But a true servant who really feels himself to be a laborer in the vineyard of Christ, will never allow himself to swerve from the path of service and follow the trail of curiosity. The Disciple who receives instructions from the Elder Brothers, is warned at the first Initiation never to use his power to gratify curiosity, and on all subsequent visits to the Temple this idea is dinned into his ears.

The distinctions between the legitimate and illegitimate use of spiritual powers are so fine and so subtle, that, as one grows, the restrictions whereby one seems beset, multiply to such an extent, that were the tale told to others, ninety out of a hundred would say: "But what is the use then of having spiritual sight or of being able to leave the body? When you are so restricted, it seems that the possibility of trespassing is multiplied to such an extent, that there is scarcely any use of having these faculties." Nevertheless, they are of great value, and the responsibility is only the natural result of added growth.

An animal takes freely anything that it wishes: it commits no sin and is not held responsible for its action, because it knows no better. But as soon as the idea of "mine" and "thine" has been imprinted upon our consciousness, then also the responsibility comes. As our knowledge grows, so does our responsibility; and the finer the soul qualities, the finer the distinctions between right and wrong. This we observe in our daily lives, that the standards of the permissible or non-permissible vary according to the quality of each individual.

And when we aspire to that power whereby we may know the past, we shall find that we are no more justified in using this power for aggrandizement, than we would be justified in using it to obtain worldly wealth or power. So the life, or the lives, we have led are hidden from us for a purpose, until we know how to unlock the door; and when we have the key we shall probably not want to use it.

For that reason, then, Siegfried is given the lethal drink the moment he enters the court of Gunther, and straightway he forgets about his past life with Mime, the dwarf, who claimed him as a son. He forgets how he forged the magic sword, "the courage of despair," which stood him in such good stead in the fight with Fafner, the spirit of passion and desire. He forgets that he had thus won the Ring of the Niebelung, the emblem of egoism, whereby he gained knowledge of his true spiritual identity and slew Mime, the personality, who wrongfully claimed to be his progenitor. He forgets how, as a free Spirit undaunted by fear, he broke the spear of Wotan, the warder of creed, and followed the bird of intuition to the abode of the sleeping spirit of truth. He forgets his marriage to her and the vow of unselfishness, implied when he gave her the ring.

But each and every one of these important events has left its impress upon his soul, and now it is to be tested: whether that impress has been deep or superficial. Temptation comes to us, life after life, until the treasure laid up in heaven has been tested and tried by temptation on Earth—whether or not it will withstand the moth of corruption. After the Baptism, when the Spirit of Christ had descended into the fleshy body of Jesus, it was taken into the wilderness of temptation to prove its weakness or its strength. And, similarly, after each heavenly experience we must expect to be brought back to Earth, that it may be learned whether we shall stand or fall in the furnace of affliction.

(You are welcome to e-mail your answers and/or comments to us. Please be sure to include the course name and Independent Study Module number in your e-mail to us.)

1. What clouded the doctrines of rebirth in the Scandinavian countries?

2. Why is it a benefit that we do not remember our past lives?

3. What idea is dinned into the ears of one who is able to search the Memory of Nature?

4. To what use should the ability to search the Memory of Nature be put?

5. What determines the fine distinction between right and wrong?

6. Why does temptation come to us life after life?

|

|

|

|

|

Contemporary Mystic Christianity |

|

|

This web page has been edited and/or excerpted from reference material, has been modified from its original version, and is in conformance with the web host's Members Terms & Conditions. This website is offered to the public by students of The Rosicrucian Teachings, and has no official affiliation with any organization. | Mobile Version | |

|