| rosanista.net | ||

| Simplified Scientific Christianity |

The Sermon on the Mount has been characterized in many different ways: It is the proclamation of the Kingdom of Heaven; an exposition of Christian morality; the goal of human living; a means of communion with God. Each reader sees it through his own eyes and praises or condemns it from his point of view. Seen through the eyes of an occult scientist, all these statements are unsatisfactory. To him the Sermon on the Mount is the chart of initiation as taught by a great Being. This Being dared to divulge the secrets of the Kingdom, knowing that they would be misunderstood and misused by countless followers and yet rediscovered time and again when circumstances would permit.

St. Matthew gave us an unsurpassed sequence of instructions for spiritual expeditions into the unknown. He arranged them in such a way that we can use them for our education. If we dare to do so, they lead us into the fathomless depths of religious experience.

The Sermon on the Mount can be understood as a treatise on spiritual diet; it teaches us that spiritual evolution means acceptance and assimilation of experiences-joyful and painful alike. The Lord's Prayer is the center of the whole Sermon.

The first section of the Sermon provides nothing less than the Magna Carta of the Kingdom of Heaven on Earth. It does not refer, however, to the Kingdom of Heaven as a realm beyond space and time. If we suppose that the promise of "rewards" in the Beatitudes can be fulfilled only after death, we deprive the Sermon of its actuality and efficacy. If we understand it as a statement about actual events in the spiritual realm here on Earth, taking place within us and within our fellow men, it will prove not only to be true, but also to be charged with power almost to the extent of being dangerous

For instance, Christ Jesus said, "Who is my mother, and who are my brothers?" (Matt. 12:48) He told His disciples: "If any man come to me, and hate not his father, and mother, and wife, and children, and brethren, and sisters, yea, and his own life also, he cannot be my disciple" — Luke 14:26. In psychological terms, this means that the individual emerges from the tribe; his personal consciousness begins to differ from the conventional consciousness of his relatives and friends. Not only do the content of his consciousness and the objects of his interest change, but his judgments, his point of view, the dynamics of his personality also are metamorphosed. The regime of Jehovah and the dominating influences of the Race Spirit begin to crumble as the Love-Wisdom Principle asserts itself in the hearts and minds of men. The human character comes of age. As a result of all this he is alone. To the orthodox, he is an outlaw, a dangerous innovator, madman, or criminal. How does he know and how do we know whether he is insane, a criminal, or a reformer?

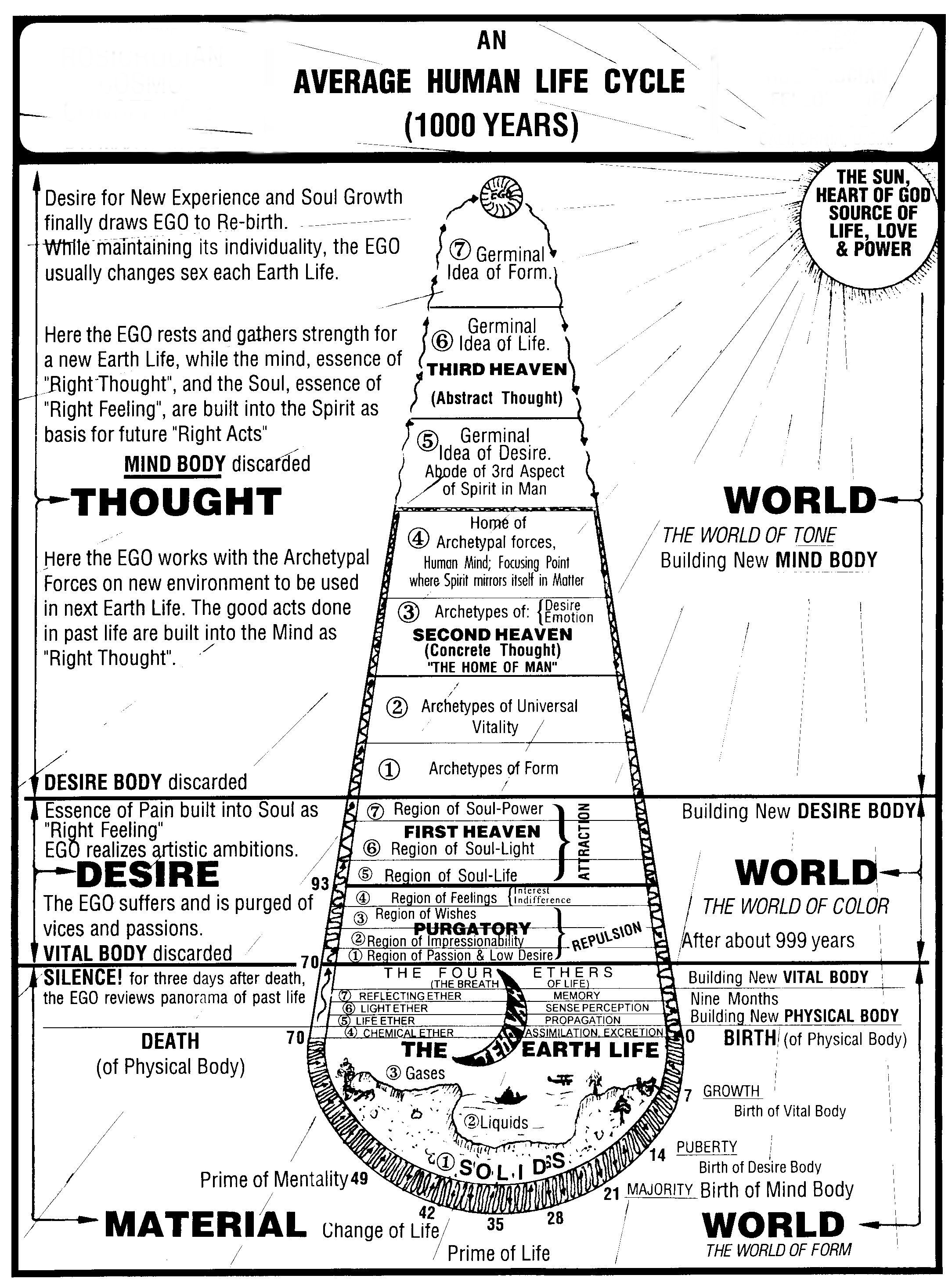

Psychology provides the terms which link our experiences closely with the development of the early Christians. Our time, like the first century, is characterized by the decay of national structure on an international scale. The individual must stick to old conventional values which are obsolete, or he must set out on his own to find entrance into the realm of the future. The new outer structure is developing within the character of the average individual. We are witnessing a psychological and spiritual mutation; the old species, homo feudalis (feudalistic man), is changing into the new species, homo communis (common man). The danger inherent in the process whereby man individualizes is egocentricity or, as Max Heindel stated: "Pride of intellect, intolerance, and impatience of restraint."

The development of individualism cannot be prevented. We cannot go back to the feudalism of tribal life. What is the way out? In religious terms, how can we act unselfishly and get rid of sin? How can we reach forgiveness and enter the Kingdom of Heaven? True Christianity presents a form of individualism, of self-reliance and independence, which allows the individual to become responsible for himself and for the group also. Individual freedom and collective responsibility coincide. The psychological process of this development is characterized by the terms individuation and integration. Its religious goal is stated in St. Paul's description of the mystical body of Christ.

Our question now is: how can we avoid egocentricity and reach individuation? Or, since we are egocentric already, how can we get rid of egocentricity and replace it with individuation? As aids, St. Matthew presents us with some of the most inspiring words in the Bible, the Beatitudes. The Beatitudes, the proclamation of the Kingdom of Heaven, convey an inner experience, a new discovery, which overthrows our natural philosophy of life. A key for inner development and the achievement of conscious growth is proclaimed in appalling, though simple, terms: nonsensical oratory to those who are not ready for it; clarifying insight and unquestionable truth to those who have passed the test of evolution; help, comfort, and remedy to those who struggle in the midst of painful transition.

The proclamation of the Kingdom consists of a series of paradoxes, built in pairs around the center. The fourth Beatitude, "Blessed are those who hunger and thirst for righteousness," means in modern language "hunger for spiritual evolution." To be discontented with our spiritual situation, to crave something better with all the recklessness of people who are starving-that is the inner situation of those who are blessed.

Nobody has this blessing as a birthright. We have to deserve it by our own endeavor. There is, of course, the danger that good news may be misunderstood and the new inheritance misused. The hardships of the journey are a safeguard, but not a sufficient one. Matthew, therefore, indicates two additional qualifications: only the meek and merciful are accepted.

Who inherits the Earth? The meek and the merciful. That the meek shall inherit the Earth has always been considered a paradox of almost sarcastic poignancy, particularly when the word meek was misunderstood to mean soft, weak, and helpless. Moffatt translates it as humble, Goodspeed as humble-minded. Gerald Heard contends it means tamed, or, more exactly, disciplined by spiritual practice, as were the Essenes. We might come closer to the truth if we construe meek as sensitive, open-minded, or, in more psychological language, without inhibitions and repressions and especially without blind spots, callousness, or dullness. We then understand that "the meek" are able to hear the inner voice, to distinguish between the creative voice of eternity and the destructive voice of egocentricity.

The fifth Beatitude accords blessing to the merciful. The Greek word for mercy corresponds to the Aramaic hisda, which means a mature state of mind characterized by understanding, sympathy, and justice. The merciful person therefore might be described as one who is completely individuated, so that he acts out of his own resourcefulness but at the same time is so sensitive to the sufferings of his fellow men that he feels them as if they were his own. The merciful are those who are mature of heart.

The two Beatitudes about the meek and the merciful form a pair of opposites surrounding the central Beatitude, which concerns the hunger for righteousness. The meek will receive the whole Earth, while the merciful will give away all they have. Surely we are reminded of the occult precept: the more we give away, the more we shall receive. If we are sensitive to other people's sufferings, we are sensitive also to the guiding intimations from beyond. Sharing our small resources with our fellow men, we are allowed to share the mercy and the creative love of the Eternal. The two opposites are two different aspects of the same evolutionary process.

The next pair of Beatitudes again form a unit contradicting and completing each other. If we learn to mourn in the right way, our mourning will turn into an experience of inner growth and the discovery of a new world with new values and new goals. It has been said that this "congratulations for bereavement" is the most paradoxical of all the beatitudes. Yet, to lose a dear friend by death always means the possibility of a new contact with the beyond and of a new turning away from the past towards the future. Such a spiritual evolution, however, takes place only if we accept, simply and honestly, without bitterness and without self-pity, the suffering which is involved, and if we search with patience and an open mind for its deeper meaning. Then desolation will be replaced by consolation, and the suffering will change into a hunger for spiritual growth.

The corresponding Beatitude, therefore, concerns the "pure in heart," or, as we might prefer to call them, the "pure in mind." To "see God," to understand His dealings with men and His purposes in history, presupposes the same lack of inhibition and absence of blind spots which characterize the meek and the merciful — in other words, a lack of egocentricity. The non-egocentric heart is courageous and honest; it is full of love and creativeness, and that means it is pure.

We discover purity of heart to have a new dynamic quality: it either grows or decreases, and it grows by experience. At least half of our experiences are negative, dealing with "evil" within ourselves or within other people. We shall have to mourn. Our problem therefore is: How can we suffer without decreasing our purity, without becoming egocentric, negative, or bitter? How can we increase our purity in spite of the suffering which is an unavoidable factor in evolution? The answer: By trying to see God, to discern the divine purpose within and behind our difficulties. This should enable us to discover deeper reasons for our suffering and to change our points of view. Seeing God is more than sensing some contact with eternity. It presupposes a humble acceptance of the "evil" in life and a forgiving of those who wrong us. This Beatitude describes the wisdom and maturity of those who have become accepted as "children of God."

The first and last Beatitudes complete the description of the dynamic process which may be called the way to Christianity, in the individual as well as in mankind. The poor in spirit will enter the Kingdom of Heaven, and the children of God will be the peacemakers on Earth. The poor in spirit will find the Kingdom, not after death but here and now, otherwise they could not become peacemakers on Earth. To be a peacemaker is a final condition without which the condition of being a recognized "Son of God" cannot be attained.

One cannot make a good peace by compromising. One has to "create" it as a new and higher form of human relationship, or else one will become an appeaser. The word creativity, with respect to humans, is absent in Greek, Aramaic, and Hebrew. All ancient languages are tribal, and therefore dumb with regard to individualism. God alone is the Creator. The fact that a man should be individually creative can be expressed only by the almost sacrilegious statement that he shall become a Son of God, a divine creative creature. This new dignity harbors a terrible temptation. Christ Jesus was able to conquer the danger, but how can we be individuated, endowed with creativity, without falling into the temptation of egocentric willfulness?

How can we be peacemakers instead of warmongers? Answer: by remaining poor in spirit. In Greek, the phrase literally means beggars regarding the spirit. Begging for spirit presupposes the knowledge that there is Spirit. All the intellectual forces that we can muster, all the energy of volition, and all the strength and subtleties of the human heart are required as tools of the Spirit.

Blessed are You When Men Revile You and Persecute You

The proclamation of the Kingdom of Heaven is a paradox. It conveys an inner experience, a new discovery, which controverts our common experience. At first this paradox is stated with philosophical aloofness: "Blessed are those..." We are asked to consider it as a general law of spiritual development. Then the text turns with sudden violence, like a pointed dagger, against the reader himself: "Blessed are you..." There is no escape; we have to answer. Is it a blessing to be reviled and persecuted? Do we feel it? Do we actually rejoice? Do we experience the reward in heaven? The "reward in heaven" must be realized immediately; loss must be felt as gain here and now, not after death. The Kingdom must be an experience of growth and evolution before we die; it may continue after death, but it must begin on Earth.

Matthew adds, "for righteousness sake and for my sake." Those who hunger and thirst for righteousness are usually at odds with their contemporaries, as were the Old Testament Prophets. There is not a blessing in every persecution; but where spiritual progress arouses the fear and fury of reactionaries and revolutionaries, there the suffering which the opposing forces inflict helps to speed the inner growth of the sufferer.

The text does not say that the people who persecute the followers of Christ Jesus are bad or selfish or malicious. They are simply people-neighbors, friends, relatives: everybody. They are like us. We are persecutors insofar as we do not participate in the evolution of mankind. We may be outstanding members of progressive or revolutionary organizations. We may say: "our economic system should change," "the millennium of the classless society should come tomorrow." The expansion of our consciousness, however, is something different. Conscious growth—the evolution of the human character—is a painful and exclusively personal task. It implies the acceptance and assimilation of our unconscious fears and faults, the removal of our inhibitions and prejudices, the reformation and integration of our passions and compulsions.

The new rules are voluntary. They cannot be enforced. The form, as Christ Jesus explains, is a system of practical experiments leading those who dare to face the tests into a new kind of religious "perfection." It is as if the disciples had asked Him: "How can we achieve meekness and purity of heart and all the other qualities of the Beatitudes?" Let us propose to give some answers. There are five different fields that we can till, as revealed in the Sermon on the Mount. These are the five steps that lead to individuation:

If you are offering your gift at the alter, and there remember that your brother has something against you, leave your gift before the altar and go be reconciled to your brother; then come and offer your gift. The tribal law, "Thou shalt not kill," was limited to members of the same tribe; outside the tribe it was honorable to kill as many Gentiles as possible. The law forbade crimes only between relatives. Christ Jesus knew that overt crimes are but the flowers and fruit of hidden roots, and that we cannot truly love our brothers and sisters unless we unearth those forgotten and repressed roots of evil. Such an unconscious hatred poisons the human mind like unknown germs; it might lead to bitterness, pessimism, and despair.

What can we do against this deadly evil if we do not know it? Certain symptoms can be diagnosed early enough. Undue anger is the first. Our brother makes an insignificant mistake and we explode as if he had wounded us to the quick. Then there is the exaggerated criticism, or a blunder, a slip of the tongue, instantly followed by the assertion that we did not mean it and are sorry. All this shows that the cancer of negativity in us is growing. We must release and change the repressed forces or they will kill us. All our religious efforts, therefore, are futile until we clean our psychic houses.

"You have heard that it was said, 'You shall not commit adultery.' But I say unto you that everyone who looks at a woman lustfully has already committed adultery with her in his heart." The central purpose of our religious self-education is to individualize without using our freedom egocentrically. Thus, we must learn to control our natural impulses, especially the sex drive, or they surely will control us.

The exact interpretation of Christ Jesus' statement is of extreme importance because the vulgar misunderstanding may produce, and indeed has produced, infinite misery. The question is: how can sexuality be honored and employed for the sake of new creation without selfish use and distortion? Matthew tells us, in the 19th chapter of his Gospel, to wait! We should not repress lust: we should admit it, accept it, and force it to wait until it turns into love.

The simile of the eye plucked out and of the hand cut off seems at first glance to describe complete mortification, and that is what thousands of ascetics have read into the text. As a matter of fact, the sex drive cannot be annihilated. It will remain alive, however deeply we repress it. It will return as a specter, haunt us as nightmares, or explode our virtuous facade by the most foolish of escapades. If our egocentricity melts away, individuation teaches us real love, and we experience its creative power. Our first task was to look without lust: now it is to look without hatred or indifference. If we cannot learn to love, at least we can learn to be fair and kind and unselfish, and that too means evolution.

"But I say to you, do not swear at all, either by heaven, for it is the throne of God, or by the earth, for it is his footstool, or by Jerusalem, for it is the city of the great King." The prohibition against swearing at all can be transcribed: Do not completely identify yourself with any plan, work, or value which you want to pursue. Be determined, yet remain flexible and adaptable. Be persevering, but not stubborn. Do not give up because men want you to, but resign gladly if you see that creation itself is going the other way.

Christ Jesus wanted the individual to emerge from life. The reborn individual finds himself in possession of creative powers and new possibilities which constitute a temptation of unexpected severity. He is free to create and to destroy. He feels as if he were God. But if he misses the right road, individuation is replaced by egocentricity, and man tries to match himself against God as his equal. The temptation is not new. But in tribal life, the law breaker is an outcast and will perish. In the new era of creation, the danger of confusing egocentric stubbornness with creative individuation is so great that the whole purpose of evolution may be thwarted by it. Max Heindel attested to this by calling the race lives and bodies we inherit "paths to destruction."

The decisive achievement which Christ Jesus wants His disciples to attain is a new kind of responsibility equal to the new creative power which will be given to them. They are the salt and the light of the Earth, but only if they remain poor in spirit. They may participate in the divine life beyond space, time, and racial identification, but if they issue rigid orders for the future, they are lost souls.

"But I say to you, Do not resist one who is evil. But if any one strikes you on the right cheek, turn to him the other also." Christ Jesus was not thinking of the new civil code without police, where bullies are allowed to exploit their victims. He speaks here of something else. He is teaching self-education. If our dignity is rooted in our creative relationship with God, a slap in the face cannot harm us. Christ Jesus' disposition when He was struck was bold and calm and of unshakable peacefulness. If we are aware of our power, feeling the contact with our Father in heaven, we are not inclined to resist evil — to fight back; we only want to serve Creation.

The principle of nonresistance must not lead to the repression of our natural urge for retaliation. The repression of the "instinct" for self-preservation would be as disastrous as the repression of our sexuality. The problem is not how to get rid of our natural instincts but how to discipline them for the sake of inner growth.

The way, as far as we can see, is this: Evil comes from outside. The evildoer attacks us. This arouses our "evil" responses-fear, hatred, bitterness, vengefulness-and therefore we resist, fight back, and the sum of evil increases. If we relax, letting the attack sweep through our bodies and minds, the suffering wakes us up more completely, removes our blind spots, and enables us to see the deep meaning of our fate.

"But I say to you, love your enemies and pray for those who persecute you, so that you may be sons of your Father who is in heaven; for He makes His Sun to rise on the evil and on the good, and sends rain on the just and on the unjust." This fifth and last of our tests follows after we have discovered in the fourth test that evildoers cannot inflict evil upon us if we do not resist evil. They can make us suffer, but this does not increase our inner darkness; all pain becomes growing pain, and we recognize the power which makes us grow.

Praying for those who persecute us means, among other things, the attempt to look at our situation from above, from the standpoint of the guiding Power of Life. Why did this Power allow our enemy to become so strong? What can he do to us? Could this be happening for our own benefit? Is it for the removal of our blind spot, to make us see more clearly, less emotionally?

Let us pray for the outer enemy as the text says, looking at him as much as we can with the eyes of the Creator, with fatherly love. He might appear as an evildoer, but we would give him a chance. Maybe we could rescue him, if we were to become peacemakers in the fullest sense of the word. However, in order to become peacemakers, we must do away with our fear, hatred, horror, bitterness-indeed, with the whole store of negative and destructive energies which the enemy conjured up from the hidden depths of our minds and which we never would have discovered without him. He has shown us what has prevented our becoming true sons of God.

The outer enemy forces us to face our inner enemies. Our inner spirit of darkness and despair is more important and more powerful than the outer enemy. Now we pray for the inner foe. How can we rescue him, redeem him, turning his darkness into the light of creation? Here is the conscious personality-incomplete, insecure, frightened; and there is the inner foe-the symbol of darkness, the fiend, the frightening and irresistible. How can the two come together? Can we love our hatred and our own anxiety? If we look from above, objectively, we discover that our hatred once was love, in early childhood, and our anxiety then was caused by frustration of our unprotected and unlimited eagerness of life.

We discover the virtue behind our vices, and we understand that darkness may be changed into light again, if only we can face it, accept it, sustain its horror, and believe in the light beyond. Jacob wrestled with the demon until it turned out to be the Angel of the Lord. Christ Jesus faced utmost darkness in Gethsemane, and by so doing entered a new phase of creation. What is our task when the unconscious opens its gates and anxiety floods our conscious mind? Let us do what all the pioneers of the inner life have done: in the battle between opposites, let us appeal to the creative center which can reconcile them on a higher level of reality. "Though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death, I will fear no evil; for thou art with me." Why should we be less courageous than the Psalmist?

These five steps or stages of growth prepare us for the climax of the Sermon on the Mount, the Lord's Prayer. Max Heindel states that this prayer may be considered an algebraic formula for the upliftment and purification of all the vehicles of man — truly a fitting capstone for the Sermon on the Mount.

— A Probationer

— Rays from the Rose Cross Magazine, March/April, 1996

|

|

|

|

|

Contemporary Mystic Christianity |

|

|

This web page has been edited and/or excerpted from reference material, has been modified from its original version, and is in conformance with the web host's Members Terms & Conditions. This website is offered to the public by students of The Rosicrucian Teachings, and has no official affiliation with any organization. | Mobile Version | |

|